The mechanical language of transformation can make us lose sight of what we are really dealing with: people. Ahead of the Transforming Together event on the 13th November, DWP Behavioural Science share how empathy, curiosity and open-mindedness lead to better assumptions about behaviour.

Blueprint, lever, reengineering… Have you ever noticed how transformation sounds like a job for engineers? The language used tricks us into seeing a social process in mechanical terms, making us lose sight of what we are really dealing with: people. The NAO may well agree, stating that some of the biggest problems with reforms have arisen when people have not behaved as departments expected

Using the logic of machines to think about organisations dehumanises change and can make a complex reality seem deceptively – and dangerously – simple. As a mental model, a crude ‘machine metaphor’ is a misunderstanding that can stop programmes from delivering their benefits, presenting poor value for money for our taxpayers and challenges for our staff.

How can we make transformation more appreciative of human realities? That is a question we’ve been focusing on here at DWP Behavioural Science, as we have been working with programmes to build more behavioural thinking into the transformation landscape. In this post, I outline three principles for making better assumptions about behaviour.

1: Empathy

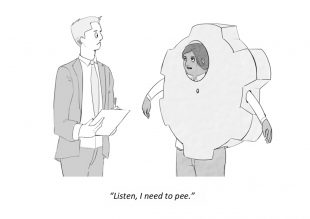

By drawing a false analogy between machines and organisations, we miss the complexity of human behaviour. The only reason machine parts do anything at all is that you made them to. Design them well and set up the machine correctly, following the rules you learned during your engineering degree, and they’ll do exactly what you want. People, however, are always already ‘on the move’, doing this and that according to their own ‘designs’ (a mix of nature and nurture), simultaneously shaping and being shaped by their material and social environment. A tricky material to build with.

Given that you cannot ‘design’ the people so that they fit the system, you have to design the system so that it works for your people. This requires knowing your people, which in turn requires empathy. Ask yourself: What is easy for them to do, given their surroundings and the situation they are in? What is difficult? Why? How could the environment be changed to make it easier for them to do what you want them to do? (Do you even know what it is – in concrete, observable terms – that you want them to do? Do they?)

UX, user research, user-centred design and service design all recognise that in designing with and for people, perspective-taking is paramount. Yet it is surprising how rarely they’re used in internal transformation. Are we mistaking our people for cogs?

2: Curiosity

You might have your own hunches about why your staff behave the way they do, and what would need to change for your programme to reach its objectives. But unless you have the empirical evidence to back them up, they are just that – hunches.

There’s plenty of material to help you investigate what affects the behaviour of your people. Many ‘user research’ methods can become ‘staff research’ methods, which you can supplement with tools from behavioural science. In our team, we regularly use COM-B, a tool created by Professor Susan Michie, looking at how factors relating to Capability (C), Opportunity (O) and Motivation (M) give rise to specific Behaviours (B). The process begins by specifying the behaviours you want to see, followed by analysing the barriers that might be getting in their way. This lays the foundation for designing more effective interventions for changing behaviour.

An example of COM-B in action is the work our team did to address staff non-compliance with security protocols, discovered during a routine sweep of one of our buildings. The initial reaction was to run a communications campaign, on the assumption that the non-compliance was either down to lack of knowledge about how to be secure (a Capability barrier) or simple laziness (a Motivational barrier).

Initially approached for guidance on comms, our team decided to dig a bit deeper. What we found surprised us. For example, in one area, we found that staff were diligently locking confidential papers away in their filing cabinets, as they should have been. However, they were then hanging these keys in a key cabinet, for which there weren’t enough keys and no clarity on who was responsible for locking it up. This unlocked key cabinet had been a major source of breaches. In this way, the curiosity that prompted research led to much more effective and efficient use of resource: focused on removing environmental barriers to desired behaviour, rather than lecturing already security-conscious staff.

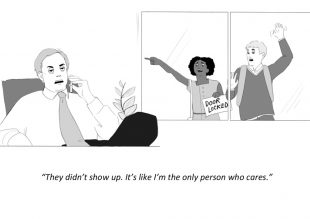

3: Open-mindedness

The machine metaphor leads to unrealistic expectations of control. When these expectations are inevitably not met, frustration and blame ensue: the problem must have been either due to a faulty part or a mistake of the engineer (who could, and should, have known better).

If you are one of the transformation engineers, you are likely to blame the parts. Psychologists have noticed that when things don’t go as we hoped, we look for causes outside of ourselves. We also tend to view the behaviour of others as caused by their internal and stable dispositions, such as character or intention.

These two tendencies, sometimes called the self-serving attributional bias and the fundamental attribution error, can help explain the power of COM-B and user research. User research harnesses empathy to look at a problem from the user perspective, which orients you towards the situational factors that you might be able to fix. COM-B systematically works through different types of barriers to desired behaviours, ensuring a holistic analysis of internal and external factors that can guide intervention design.

The attribution of security breaches to negligence, in the example discussed above, looks like a textbook example of attributional bias. Without consciously countering our tendencies, we risk basing interventions on false assumptions, wasting resources and alienating our staff while doing little to solve the real problem. Remaining open to new information can be uncomfortable – especially if it requires admitting that we were wrong, or that policies and procedures we’ve already built are contributing to the behaviour we don’t want to see. But it is necessary for keeping us grounded in reality.

We hope that you will join us in this conversation in the comment box below – as well as joining us at Transforming Together 2019. Registration for the event is now closed but if you would like to be added to the waiting list please contact transforming.together.2019@digital.cabinet-office.gov.uk

Taru Tiililä - Behavioural Science- Department for Work & Pensions

Illustrations by Claire Ferguson - Behavioural Science - Department for Work & Pensions